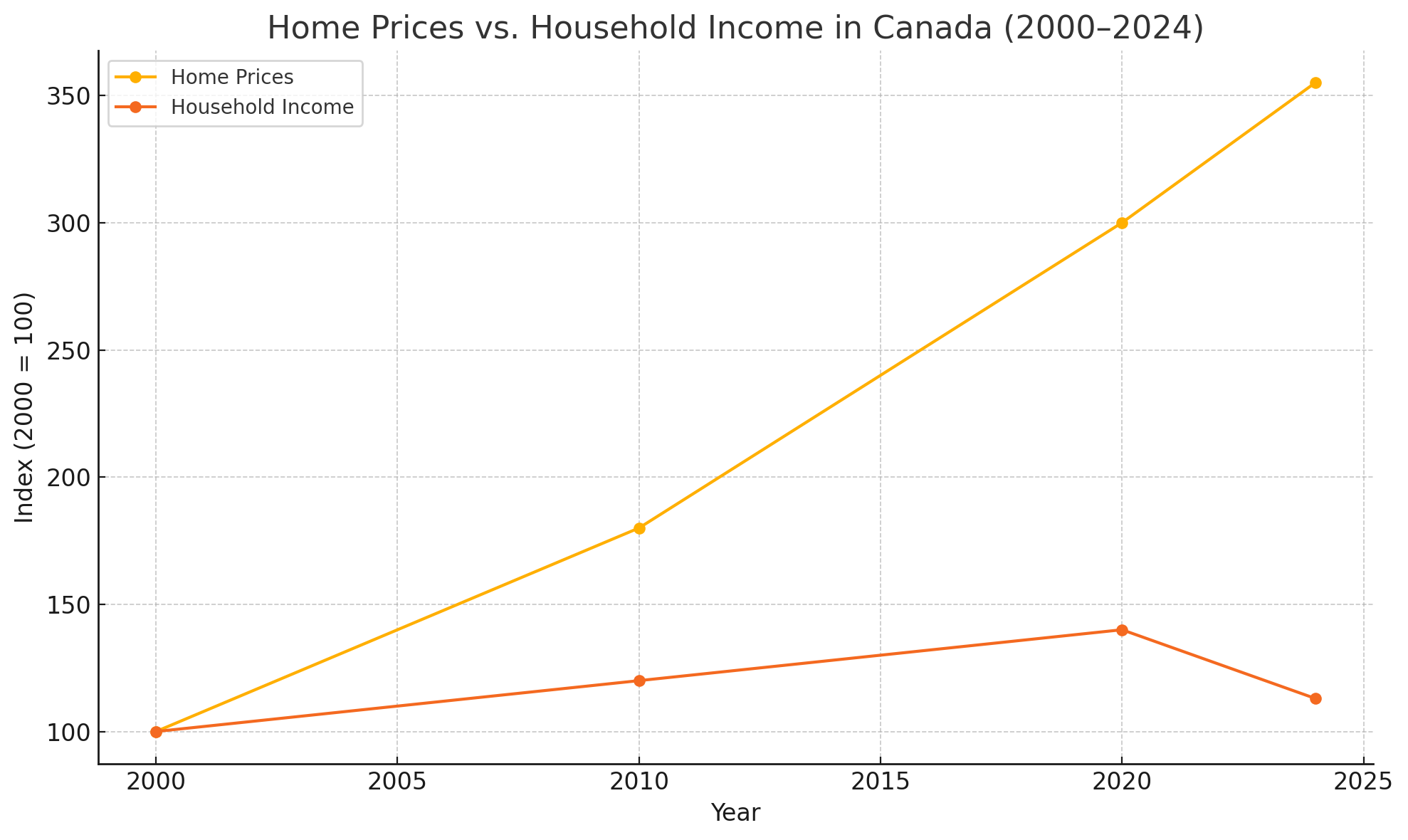

Canada is in the throes of a housing crisis defined by sky-high prices and a dire shortage of affordable homes. By 2021, Canadian home prices had surged 355% since 2000 while household incomes rose only 113%.

This has made Canada one of the least affordable housing markets in the world.

Renting offers little relief: rents have been climbing at roughly double the rate of inflation, with increasing overcrowding and homelessness as a result mpamag.com.

Meanwhile, the country’s population is growing rapidly, adding pressure to a housing supply that isn’t keeping up. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) projects we need about 5.8 million new homes by 2030 to restore affordability – a massive goal we are far from on track to meet multiculturalmeanderings.com .

How did we get here?

For decades, housing policy has treated homes as investment assets rather than a basic necessity mpamag.com.

Since the 1990s, Canada pulled back on public housing programs, relying on the private market to provide shelter mpamag.com.

Here’s a chart showing how Canadian home prices have dramatically outpaced household incomes from 2000 to 2024. This visual clearly supports the article’s point about affordability deteriorating over time.

CMHC Homes Needed vs. Projected (2024–2030) – Highlights the growing shortfall in housing supply needed to restore affordability.

Average Rent by Province (2020 vs. 2024) – Shows how rents have surged in several provinces.

Housing Type Distribution in Canada – Demonstrates the small share of social and public housing compared to private ownership and rentals.

Land Use for Affordable Housing Projects – Illustrates potential sources of land for new affordable housing.

The result is a perfect storm of low supply and high demand, where owning or even renting a decent home is out of reach for many Canadians. Solving this crisis will require bold, creative action on multiple fronts – there is no single silver bullet. Below, we outline seven ambitious but entirely doable solutions that address both affordability and supply. Each idea is inspired by expert recommendations (as highlighted in Maclean’s magazine) and real-world examples of positive change.

1. Implement a National Social-Housing Program

One fundamental solution is to bring back a robust national social-housing program – a federally-led effort to build non-market housing (such as public, co-op, and non-profit homes) at a large scale. Canada once had strong social housing initiatives: before 1993, federal programs helped create hundreds of thousands of affordable units across the country mpamag.com. But funding was withdrawn in the early 1990s, and construction of social housing plummeted. Today, only a tiny fraction of Canadian housing is publicly funded, leaving us with “one of the lowest rates of social housing in the world,” according to housing researcher Carolyn Whitzman multiculturalmeanderings.com.

Reviving a national housing program would mean direct government investment to build affordable homes that remain outside the speculative market. This could include new subsidized rentals, community housing projects, and supportive housing for vulnerable groups. Other wealthy countries offer models: many European cities are building beautiful, affordable public housing and co-operatives at a faster pace than Canada oakland.overdrive.com.

For example, Vienna and Singapore have successfully maintained extensive social housing that keeps rents reasonable for citizens. A Canadian national program could similarly create hundreds of thousands of permanently affordable units, easing pressure on the private market. Importantly, it would treat housing as essential infrastructure – like schools or hospitals – rather than a commodity. As Whitzman notes, back in the 1970s (another period of high immigration and population growth) Canada actually built more housing than we do today, precisely because we had robust federal programs and incentives for purpose-built rental housing multiculturalmeanderings.com.

Re-establishing such a program now would directly increase supply at the low-cost end, provide homes for those in core need, and help make housing a human right in practice, not just in principle.

2. Reform Zoning Laws to Allow Greater Density

Another key to unlocking supply and affordability is overhauling restrictive zoning laws. In many Canadian cities, outdated municipal zoning rules forbid multi-unit housing on the majority of residential land, effectively mandating sprawl and scarcity. These rules – often called single-family zoning – mean that on a given lot it may be illegal to build anything other than a detached house. This strangles the creation of townhomes, duplexes, small apartment buildings, and other denser, more affordable forms of housing. As Maclean’s bluntly puts it: too many local governments “refuse to allow the housing abundance Canada needs,” and it’s time for higher levels of government to step in oakland.overdrive.com.

Reforming zoning laws would involve allowing greater density, especially in urban and suburban neighborhoods well-served by transit and infrastructure. Provinces or cities could change rules to permit duplexes, triplexes and garden suites on lots that currently allow only single houses. They can also pre-zone more areas for mid-rise apartment buildings and mixed-use development. Some progress is underway – for instance, cities like Edmonton and Minneapolis have already eliminated single-family-only zoning, and Ontario has moved to legalize duplexes and triplexes on most residential lots. But much more needs doing across the country. By embracing “gentle density” and mid-rise development, communities can add housing supply without altering neighborhood character drastically. Even modest densification can have a big impact: imagine if every block in a city added a couple of duplexes or a small apartment – it would create thousands of new homes over time. Denser housing forms are also generally cheaper per unit, making home ownership or rent more attainable. Governments beyond the local level may need to incentivize or mandate zoning changes if cities drag their feet. The bottom line is that zoning must evolve to accommodate Canadian families’ needs, not block them. Unlocking zoning constraints will open up space for builders to construct the missing middle housing (townhomes, multiplexes, low-rises) that can fill the gap between single houses and high-rise condos.

3. Invest in High-Speed Rail to Connect Urban and Rural Regions

It might not be obvious at first, but transportation policy can be housing policy. A bold proposal in the mix is to build high-speed rail lines linking major cities with smaller towns and rural areas. The idea: fast trains would “connect inexpensive communities to bustling urban labour markets”, making it feasible for people to live in more affordable regions while working in big-city jobs oakland.overdrive.com. In essence, Canada isn’t short on land – we’re short on connected land. By shrinking travel times, high-speed rail can vastly expand the range of housing options accessible to Canadians.

Imagine being able to commute from a town 200 km away to a downtown office in under an hour thanks to a bullet train. Suddenly, a house in a small city or rural area (where prices are much lower and space is ample) becomes a viable home for someone who works in Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver. This takes pressure off the overheated urban housing markets and distributes demand more evenly. As one advocate explained, “we’re a country that’s not short of land, what we’re short of is connected land,” and fast rail can bridge that gap voicetube.com.

Countries like Japan, France, and Spain have used high-speed rail to successfully decentralize growth – people can live in regional cities and still participate in the economy of major hubs. In Canada, strategic rail corridors (for example, Toronto-Ottawa-Montreal or Edmonton-Calgary) could open up new housing frontiers. High-speed rail investments would also create jobs and environmental benefits (by reducing car dependence). Of course, these projects are expensive and long-term – but their impact can be transformative. Faster, more frequent inter-city trains would knit our communities closer together. With improved transit connections, young families might find it realistic to buy an affordable home in a smaller community and still pursue opportunities in a larger centre. Housing affordability isn’t just about building more homes where people already live, but also about connecting people to where homes are more affordable. High-speed rail is a visionary way to do exactly that oakland.overdrive.com.

4. Repurpose Surplus Public Lands for Affordable Housing

All levels of government own vast lands and properties – from empty lots to underused office buildings – that could be unlocked for housing. Repurposing surplus public land for affordable housing is a solution hiding in plain sight. The federal government has already identified and started releasing some surplus lands (many of them former office complexes with big parking lots) for development of new homes macleans.ca. This is a great start, but we need to go much further. Maclean’s notes that underused public land could house hundreds of thousands of Canadians if made available oakland.overdrive.com.

Instead of sitting idle or being sold off to the highest bidder for luxury condos, public lands can be retained for projects that maximize public benefit: mixed-income housing, non-profit developments, or other affordable homes.

Consider the possibilities: a disused government warehouse could be converted into loft apartments; a vacant city-owned lot could become a site for co-op housing; surplus school board lands or parking lots could host new mid-rise residential buildings. Because the land is already publicly owned, these projects could dramatically cut costs – one of the biggest expenses in housing is land acquisition. By offering public land at low or no cost to affordable housing providers, governments can spur construction of homes that ordinary Canadians can afford. We’ve seen promising examples: some municipalities are mapping their unused parcels for housing initiatives, and Crown corporations like Canada Lands Company have turned former military bases into civilian communities. In Mississauga, for instance, surplus federal lands are being leveraged to build thousands of new housing units as part of development plans discountmags.ca.

Additionally, partnerships can be formed to include community amenities (parks, community centers) alongside housing on these lands, creating vibrant new neighborhoods. Every level of government – federal, provincial, municipal – should conduct an audit of property holdings and fast-track any “lazy land” into the pipeline for affordable housing. By turning parking lots and empty buildings into homes, we not only increase supply but also revitalize areas for public good. It’s a win-win strategy to make use of resources we already have.

5. Support Innovative Housing Models like Tiny Home Communities

Tackling the housing crisis also means thinking outside the typical real-estate box. One innovative approach gaining traction is the development of tiny home communities and other alternative housing models. Tiny homes – usually under 300 square feet – can be built quickly and cheaply, providing immediate shelter for people who might otherwise be unhoused or unable to afford a conventional house. Maclean’s highlighted a striking example: in Gatineau, Quebec, a village of brightly colored shipping-container tiny homes has been established in a parking lot, pointing the way out of homelessness for its residents oakland.overdrive.com.

These micro-dwelling communities offer safety, dignity, and privacy at a fraction of the cost of traditional housing.

One of the most inspiring case studies is the 12 Neighbours project in Fredericton, New Brunswick. This initiative, started in 2021 by local tech millionaire Marcel LeBrun, set out to create a community of 99 affordable tiny homes for people in need en.wikipedia.org. In just two years, 96 tiny houses have been built – roughly one new home every week – and the community is now complete globalnews.ca.

Each small home is permanent, comfortable, and paired with supports on-site to help residents rebuild their lives. LeBrun’s vision was not just to give people a roof overhead, but to foster a supportive village where “the community becomes the healing agent.” Indeed, residents like “Mayor Al” – a former homeless man who earned his affectionate nickname among neighbours – have experienced life-changing improvements since moving in, gaining stability, purpose and a sense of belonging globalnews.ca. Projects like 12 Neighbours demonstrate how innovative models can make a real dent in homelessness and housing insecurity.

Beyond tiny homes, other novel housing ideas include modular prefab housing (factory-built units that can be assembled rapidly on-site), laneway suites and backyard homes (small dwellings on existing properties), and co-living arrangements that blend private and shared spaces to cut costs. Embracing these innovations can quickly add flexible, affordable options to our housing mix. Not every household needs or wants a full-size traditional house. By supporting pilot projects and scaling up successes like the Gatineau container village or Fredericton’s 12 Neighbours, governments and communities can diversify the housing supply. These models often face zoning or code barriers (for example, minimum unit size rules or NIMBY resistance), so part of the solution is adjusting regulations to allow creative approaches. Ultimately, every Canadian needs a safe, dignified home, and innovative models are proving that we can deliver housing in new, cost-effective ways – whether it’s a cluster of tiny houses, a converted shipping container, or a modular apartment building. We should encourage this kind of experimentation, and when it works, expand it across the country.

6. Introduce a “Gentrification Tax” to Curb Speculative Investment

Runaway housing prices aren’t just a product of supply and demand – they’re also driven by speculation and investment treating homes as commodities. To temper this and capture value for the public, some experts propose a “gentrification tax” or similar measures to rein in speculative gains. The concept is to tax the windfall profits that flippers, speculators, and even long-term owners reap from rapidly rising property values, and then reinvest that money in affordable housing initiatives linkedin.com, canadianarchitect.com. In other words, when someone sells a property for a huge profit simply because the market spiked (not due to their own improvements), a portion of that unearned gain would go back to the community.

One specific proposal, championed by groups like Architects Against Housing Alienation (AAHA) in Toronto, is a Gentrification Tax on home sales. For example, a tax could be applied to the sale of residential real estate in gentrifying neighborhoods, where property values have shot up. The funds from this tax would be earmarked to buy or build deeply affordable housing, likely through community land trusts or non-profits canadianarchitect.com. This helps offset the displacement effect of gentrification by directly funding new affordable units in the area. Another variant, suggested by UBC’s Generation Squeeze lab, is a surtax on expensive homes nationwide – such as a modest annual tax on homes valued above $1 million linkedin.com. That proposal, published in Macleans’, envisioned a 0.2% tax on $1M+ homes (scaling up to 1% on $2M+ homes) which could raise $5 billion annually for housing affordability programs linkedin.com. Critics cried foul at the idea of taxing home equity, but it highlights a key point: Canada’s housing wealth has ballooned so much that even a tiny levy on the top end could generate significant funding to help those left behind in this market.

The goal of these taxes is two-fold: deter pure speculation (by reducing the easy windfalls that attract speculative buyers) and generate revenue to invest in housing solutions. We’ve already seen governments use taxation to cool the market – for instance, British Columbia’s Speculation and Vacancy Tax and Foreign Buyers Tax helped somewhat to deter non-resident speculators and reintroduced vacant units back onto the rental market. A gentrification or windfall tax would take this a step further by addressing domestic speculation and the rapid equity gains longtime owners have seen. Of course, such policies must be designed carefully to target true windfalls and not unduly burden average homeowners. But if oil companies can face windfall taxes during profit booms, the argument goes, why not capture some excess housing profits to benefit societylinkedin.com? By putting a price on speculative investment, we can send a signal that homes exist to house people first and foremost. The proceeds can then help fund the social housing, rental supports, and other measures needed to fix the crisis. It’s a bold idea, but one that forces a much-needed conversation about housing as a shared public good.

7. Expand Rent Control Policies to Protect Tenants

While we work on adding new housing, we must also protect those Canadians already housed but struggling with ever-rising rents. Expanding and strengthening rent control is a crucial solution to prevent evictions and instability for millions of renters. Rent control refers to laws that limit how much landlords can increase rents annually and under what conditions. Right now, rent control in Canada is a patchwork: some provinces like Ontario and BC have annual caps on rent hikes (tied roughly to inflation), but there are major exceptions. For instance, Ontario exempts all new rental units first occupied after November 2018 from rent control entirely macleans.ca , meaning if you live in a newer building, your landlord can raise the rent by any amount each year. This often leads to huge spikes or the practice of “renovictions” (landlords evicting tenants under the guise of renovations, then re-renting at a much higher price). Such loopholes erode affordability and put tenants constantly at risk of being priced out.

To fix this, governments should consider broadening rent control to cover more units and closing loopholes. An expanded rent control regime might include vacancy control – tying the cap to the unit, so landlords can’t circumvent the rules by switching tenants. It could also apply to currently exempted units, so that all renters have basic protections no matter when their home was built. Critics of rent control often claim it discourages developers from building rentals. But a balanced approach can address those concerns (for example, by offering developers other incentives to build, or by exempting the first couple of years of a new building before controls kick in). The priority is to stop the bleeding for tenants here and now. Rents in many cities have seen double-digit percentage jumps year-over-year, far outpacing incomes. This has led to situations where families must move far away, downsize dramatically, or end up homeless because they can’t absorb a sudden rent hike. Stronger rent control can temper these increases. For example, British Columbia has a province-wide annual cap (2% for 2023) and disallows additional increases above that except in limited cases – a policy that provides renters some predictability.

By expanding rent controls, we buy time for renters until more housing supply comes online. It is essentially a consumer protection measure: just as we have interest rate caps or utility price regulation to prevent gouging, rent regulation protects people from extreme housing cost shocks. Importantly, rent control should be paired with better tenant rights enforcement – such as accessible tribunals to challenge illegal evictions or hikes – so that the rules have real teeth. In the bigger picture, keeping Canadians housed stably is not just an economic issue but a social one: when people aren’t worried about losing their home, they can invest in their communities, their jobs, and their family’s future. Expanding these protections is a signal that we value the housing security of renters (who make up about one-third of Canadian households) as much as the interests of investors. Over the long run, more fundamental solutions (like building more units) will ease pressure on rents, but until then, rent control is a critical safeguard to ensure the crisis doesn’t deepen for those at the mercy of the current market.

Conclusion: Turning Bold Ideas into Action

Canada’s housing crisis wasn’t created overnight, and it won’t be solved with half-measures. The strategies outlined above – from a national social-housing program to rent controls – are ambitious, interconnected solutions that together address both the supply of homes and the affordability of those homes. Each idea reinforces the others: for instance, using public land for social housing can produce affordable units quickly, while stronger tenant protections prevent displacement as neighborhoods change. Implementing these solutions will require political will, coordination across governments, and broad public support. This is where concerned citizens and stakeholders come in. We need to collectively insist that housing be treated as a top priority and a basic human right. That might mean urging our leaders to invest budget dollars in housing programs, supporting zoning changes in our neighborhoods, or voting for policies that tax speculative gains to fund affordable homes.

The broader implication of all these ideas is a re-balancing of our approach to housing. Do we see housing as mere real estate, or as the foundation of healthy communities? The status quo has left too many people locked out and anxious about the future. By contrast, the vision behind these solutions is a Canada where everyone can find a decent place to live at a reasonable cost, whether they are a young adult starting out, a family building a life, or a senior on a fixed income. Imagine the ripple effects of solving this crisis: more young Canadians could form households and start families without crippling debt news.ubc.ca; employers in expensive cities could attract workers who no longer fear unaffordable rent; neighborhoods could stay diverse and vibrant instead of pricing out all but the wealthy. Ultimately, fixing the housing crisis is about building the kind of society we want – one that values inclusion, stability, and opportunity.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge, but the examples we’ve discussed (like Fredericton’s tiny home village, or cities that have successfully up-zoned) show that progress is possible. Each bold idea starts with a single step: a pilot project, a new law, a community initiative. As individuals, we can educate ourselves and others about these solutions, push back against NIMBYism (“not in my backyard” resistance to new housing), and support organizations making a difference. Perhaps most importantly, we can reframe housing in our national conversation – from a lottery of sky-high prices to a collective project of nation-building. Canada has overcome housing shortages in the past when it had a “we’re all in this together” mentality, such as the post-war era that built middle-class suburbs and the 1970s programs that developed co-ops and public housing. We can do it again, updated for the 21st century.

The housing crisis may be complex, but it is not insurmountable. By embracing these seven solutions – and treating them with the urgency and boldness that the situation demands – we can make tangible progress. It’s time to turn these ideas into action. The sooner we start, the sooner we make Canada affordable again for all. Each of us has a stake in this outcome, and each of us can be part of the solution. Let’s build a future where every Canadian has a place to call home. Homes for all – it’s entirely within our reach, if we choose to make it happen. oakland.overdrive.com

Sources:

Maclean’s, “How to Fix Canada’s Housing Crisis” (Mar. 2025 cover story)

· Treleaven, Sarah. Maclean’s: “How one Canadian tech millionaire built a tiny-home community” (Feb. 5, 2024) en.wikipedia.org

Mendoza, Candy. Canadian Mortgage Professional: “Canada’s housing crisis: Why it’s more than just supply and demand” (Oct. 7, 2024) mpamag.com

Whitzman, Carolyn – Interview in Maclean’s: “Stopping immigration won’t fix Canada’s housing crisis” (Sept. 2023) multiculturalmeanderings.com

Reuters: “Canada's housing affordability crisis may persist for years” (Sept. 30, 2024)

Global News: “Fredericton tiny home community providing housing, opportunity” (Apr. 20, 2024) globalnews.ca

· Architects Against Housing Alienation (AAHA) – Not For Sale! campaign demands (2023)

Steve Pomeroy, summary of Macleans (Aug. 2022): proposal to tax windfall housing gains

and Generation Squeeze report. linkedin.com